People love organically grown old towns. The stylistic variety and cohesion nurtured over hundreds of years anchors us in history while simultaneously acknowledging and showcasing our modern capabilities.

Union Square, San Francisco

This is true in many older towns around the world. These places have endured and benefited from innumerous and often controversial transformations and additions over time. Recently, their most inner cores have become lively shopping districts and pedestrian friendly zones – providing a valuable tax base many cities depend on.

Over here in the western US, not all our cities have a history that started before the dominance of the automobil. Suburban sprawl and automobile centered zoning has often discouraged this kind of cohesively grown urban environment to emerge. Recognizing this deficit, many cities today have set out to recreate it. But – how does one start when “there is no there there”, as Gertrude Stein once so aptly put it?

downtown Dana Point, 2009

Urban environments are successful largely due to the dialogue between its components, and less so because of the grandeur of an individual structure. Not that the occasional civic masterpiece does not matter, but it is the context - the tension between narrow and open, between high and low, bright and subdued, solid and playful, density and open space, important structure and background building, old and new – that makes grown urbanities uniquely attractive.

The way old towns started is very simple – after the first structure was built, somebody reacted to it with the next project, and then the next project reacted to those two, and so on. This often took place for hundreds of years. The rich tapestry we admire today is the result of many of these interactions.

In order to create new downtowns from scratch, this reactive-ness is the secret life force that will need to be jumpstarted at first, and maintained and supported later.

This will require a rethinking of much of the design language and zoning rules we have become accustomed to. Rather than create an all around formally resolved building, it is more important to design new projects with formally 'open ends', so that the subsequent projects then can pick up the uban narrative and continue it. This 'starter culture' functions similar to the 'starter culture' in the creation of a new wine. The small injection of yeast mobilizes the natural yeasts and sugars in the grape juice to create the liquid masterpiece.

We find examples of this principle on mainstreets everywhere. Buildings have proud front facades, but the sides are designed for connections and continuation.

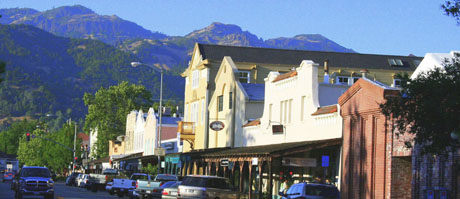

typical California Main Street

A successful urban dialog, refined over a span of time, is always visible in the urban fabric. We found that for new downtowns, especially for the first projects, it is important to create a back story that could have guided the designs at the beginnings of the downtown, had all that happened a while ago. This is similar to writing a movie script, where new screen characters are so much more credible if they have a believably rich and detailed pretend-history. For a new lively downtown, a back story is never the reason-d’etre per-se, but is only the ‘starter culture’ that will allow the perpetual urban process to begin. Once genuine urbanity takes hold, after a while, the back story will no longer be important, and it’s traces might even disappear and become superseded by real history instead.

'The Pointe' in Dana Point

We found a successful urban 'starter' environment has the following ingredients:

... a series of pedestrian spaces, connected to each other

... a series of different real buildings, or ‘virtual’ buildings (breaking down one larger building’s mass to look as if it was a series of different buildings, created by different people, over time)

... a variety of formal styles, with some reaching back to more historic examples

... a variety of materials on different buildings, even virtual buildings

...a variety of facade proportions over different buildings; while individual buildings could be very simple by themselves – as they often are in real grown town, different building should nevertheless exhibit different sill heights, opening proportions, different spacing for window axis, different roof configurations, etc.

To make such environments most believable even if they are built at once, they get best finished by different groups of contractors, so that even the individual characteristics of a particular set of hands can leave an identifiable imprint on one or more of the buildings, but not on all of them.

Such downtowns are successful and resonate with the public. This design tool has been employed with shopping malls for many years. Starting with Horton Plaza in San Diego

to many of Rick Caruso’s successful properties, like the Grove in Los Angeles

the concept has proven its’ public appeal and financial success many times over. For a real ‘downtown starter’, unlike in a mall, the ‘trick’ is to build tension into the design somebody will have to react to in the future, with another project.

With that, the downtown will gain its own life and eventually become an ever changing and adapting organism, rather than a one-off snapshot of a pretty urban place somewhere else.\

Downtown Santa Cruz

Santa Monica, Third Street Promenade